I have a confession to make. Sometimes I write a blog to clear up my own confusion, which often happens when my own values run into potentially contradictory data. This is one of those blogs. The three sides of the triangle I’m trying to square are

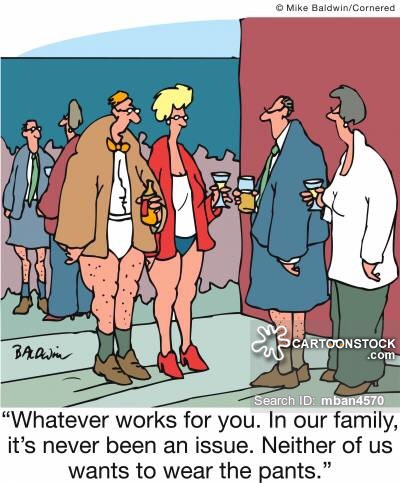

- Gender equality. If I was a woman, I’d be happy to be called feminist, but I’m male, and any discussion of equality must involve both genders.

- Human reproduction. We’re good at this, it’s part of us, and it defines areas of complementarity rather than equality.

- Economics. This is the creation and distribution of value. Unfortunately, value is not infinite, and is hard to grow.

Let’s start by reviewing the evidence against gender equality. This comes in three flavours, ranging from the silly to the plausible. I’ll start at the silly end, with the idea that women are inferior to men.

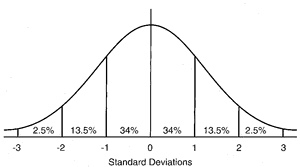

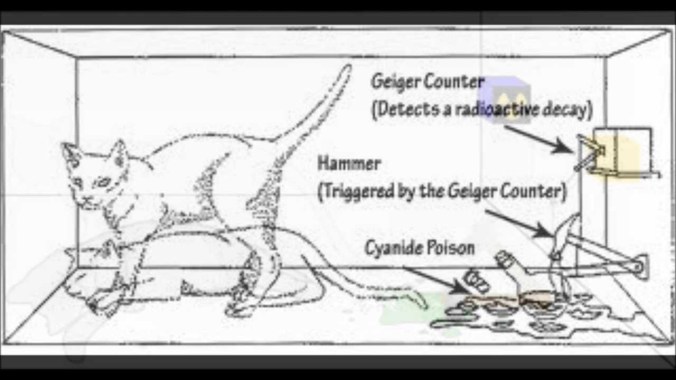

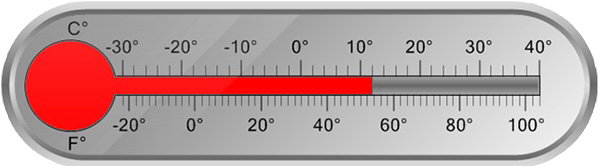

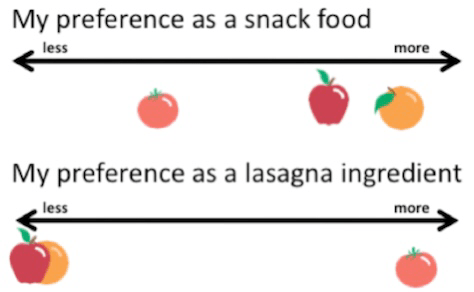

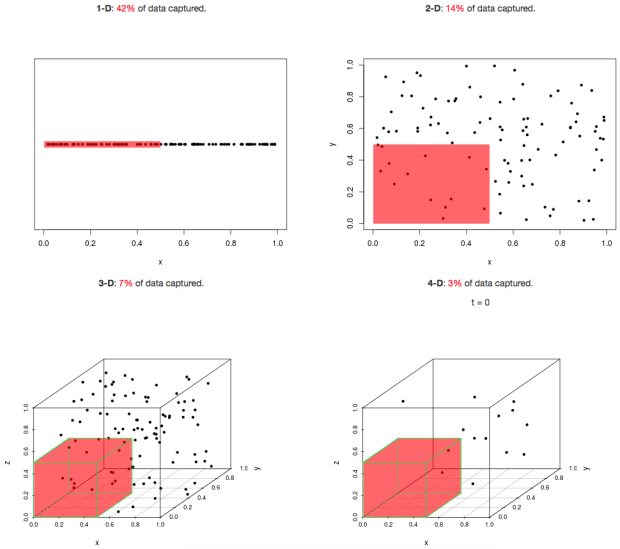

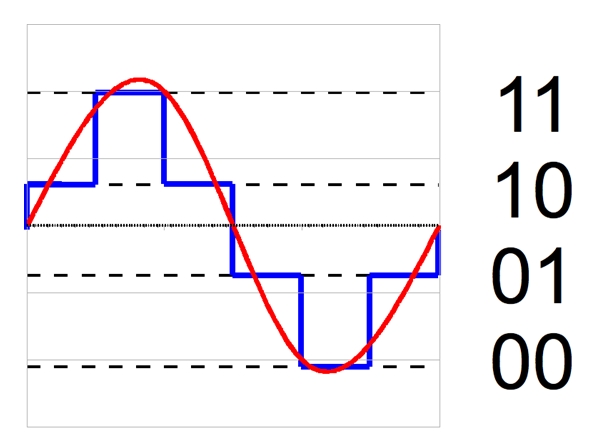

If you weren’t thinking hard, you might want to cite the chart above as partial proof of this point. However, what it also shows is that a) some women are stronger than some men, and b) as we’re judging strength, not gender, we’re judging apples as if they were oranges. We might as well complain that a submarine can’t fly.

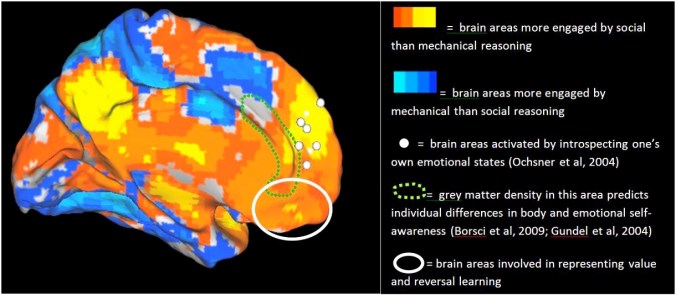

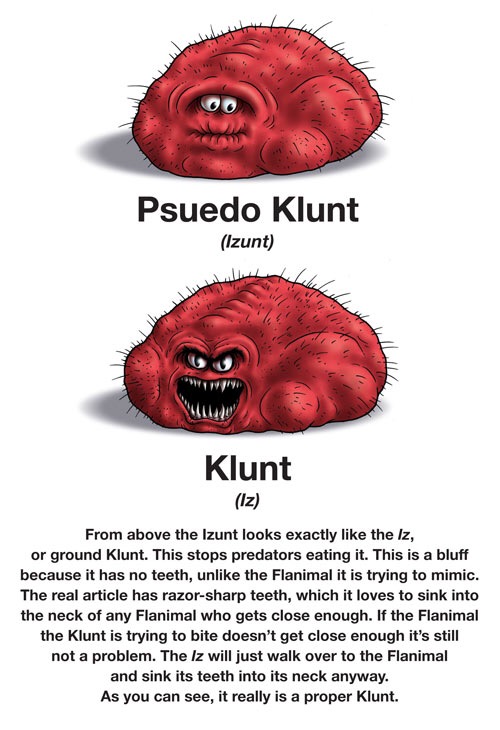

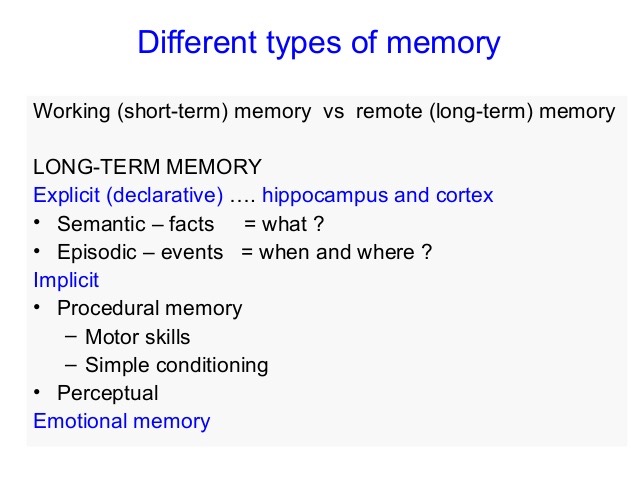

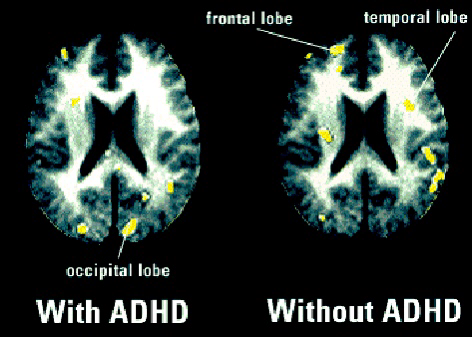

The second argument is captured in the pop-psychology best seller “Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus”.

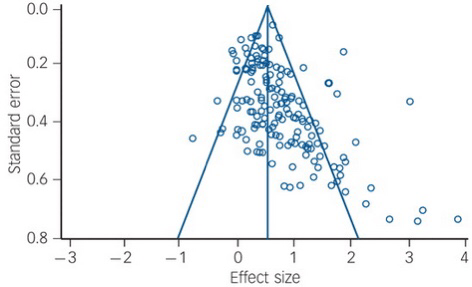

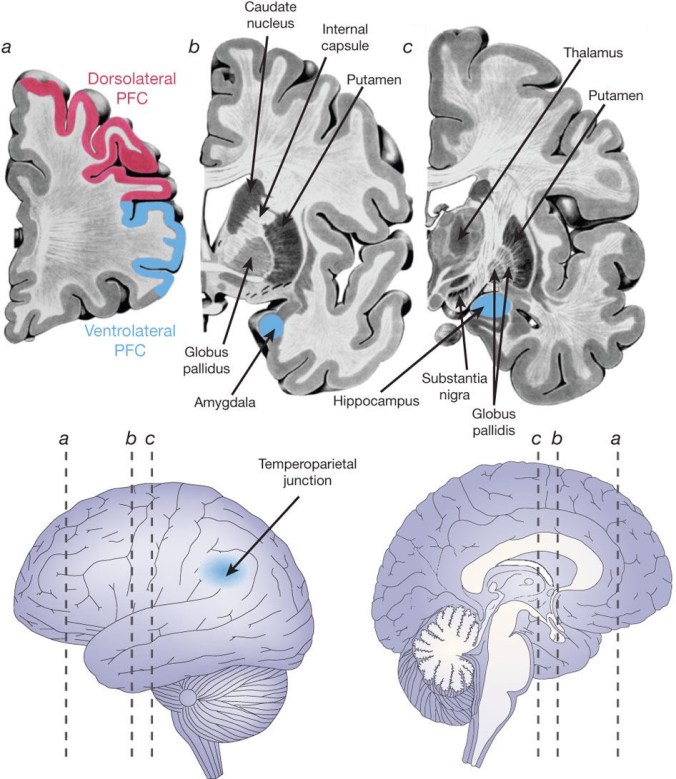

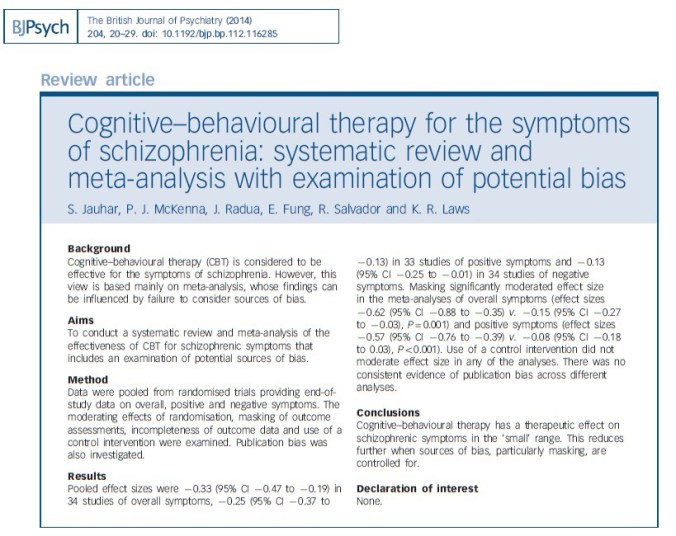

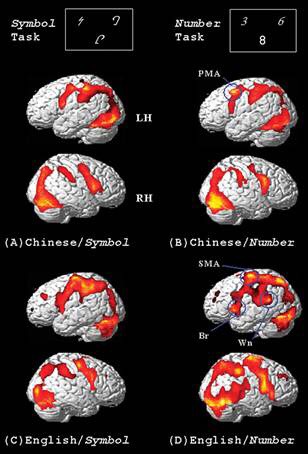

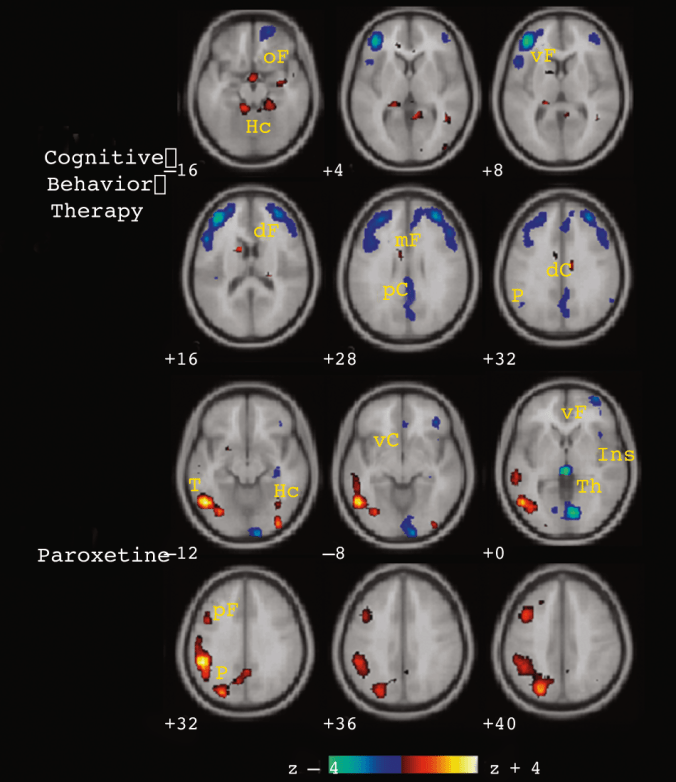

This conceptual horror has blighted the public lives of a whole generation of cognitive psychologists, who have to explain that it’s really that men show higher degrees of variability & subtle differences in brain connectivity, which translate into rather small differences in some cognitive abilities, of dubious importance.

For example, the famous linguistic superiority of women has an effect size of 0.11, which the researchers considered is too small to reliably measure. The difference in female sensitivity to non-verbal cues was not much larger, at 0.19. This translates into a woman having only a 6% chance of having higher skill in this area than a randomly selected man. Looking in the other direction, the visuospatial superiority for men has an effect size of around 0.17.

The third argument usually dresses itself up as evolutionary biology, and argues that men and women are differently optimised, as hunter-gatherers and homemakers respectively. Unfortunately, this begs the question of why we have different genders in the first place. Both on theoretical and experimental grounds, it seems that males represent represent a significant evolutionary cost, for which no benefit has yet been conclusively identified. Additionally, computer simulations of family evolution (the only experimental test available), which included gender differences, did not report gender specialisation, but a general cooperation factor as being most relevant to survival. This general cooperation factor arose from social learning, not genetic mutation. Curiously, the researchers found that variation in environmental adversity predicted a slightly lower level of this factor than unvarying adversity. Thus, there is no evidence that natural selection would select for men having worse homemaking inclinations than women, though levels of cooperation might vary for both: we have already seen that their aptitudes are very similar. It does support the view that gender role differences are likely to be learned, fluid, and based around cooperation to address environmental needs.

It’s nice when the science confirms one’s values!

Reproduction

Whatever we may think of our own reproductive careers, as a species humanity has been enormously successful: there is almost no land environment on earth which humans have not been able to establish societies in. As reproductive strategy (to provide random mutations at an appropriate rate and variety) is the other side of natural selection, we must be getting it right. An obvious feature of our strategy is that we are sexually dimorphic. As we have just seen, it isn’t possible to say what advantage this brings, as we have no idea what the advantage of being gendered is. From what we have just argued, it follows that there will be some role differences based on this dimorphism, communicated by social learning, and variable according to circumstances. An obvious example is the way, in some societies, women take over previously male labouring roles in wartime, despite their strength differences, and retreat from them when peace returns.

This naturally raises the question of whether there are any role differences which are permanent across societies, qualitatively if not quantitatively. Because of our sexual dimorphism, it makes sense to look for such roles in connection with our choices of sexual partner. What, other than appearance, do we find sexually attractive about each other? Secondly, three of our sexually dimorphic physical characteristics, height, strength and hair length, are shared by both genders. Does variation in such physical characteristics lead to gender-related role differences in the same gender?

Sexually attractive characteristics

In children of both genders, awareness of attractiveness develops early, with awareness of female attractiveness developing both earlier and more intensely than male attractiveness.

This bias for attractiveness may be biologically mediated. Consistent with the implication that male attractive qualities are less observable, women reference their choices with respect to other women. There may also be a safety component in this, as British undergraduate women find the “dark triad” personality traits of narcissism, Machiavellianism and psychopathy significantly attractive: clearly these are things one can easily have too much of.

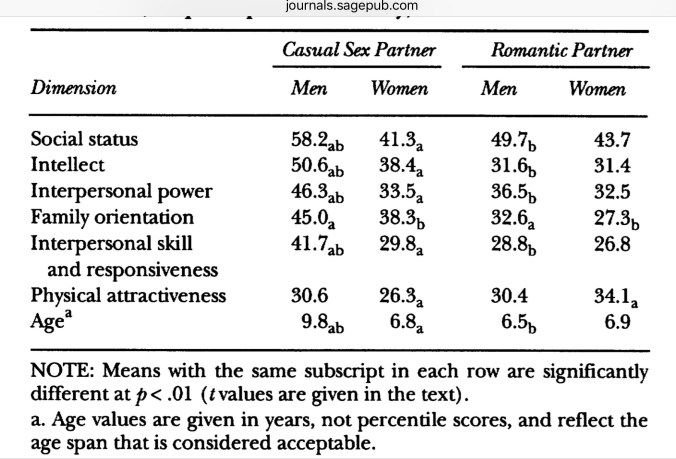

Fortunately, this is counterbalanced by also seeking empathy among male friends, and of course observation of empathy requires paying attention to men’s interactions with women. These “dark triad” findings alert us that sexual choice may be more than just liking, and if we recall that economics is the social science of value it then makes sense that much psychology focuses on sexual choice as a form of economic exchange, particularly when it comes to choosing long term partners. A recent study illustrates how this might differentially affect partner choice. When producing children, we want to give them the best start in life possible, and acquiring the best partner to make them with is therefore a no-brainer. This has been conceptualised as “mate value”, which has been broken down as follows:

- Physical attractiveness

- Personality

- Education

- Intelligence

- Career prospects (aka earning potential)

- Social status

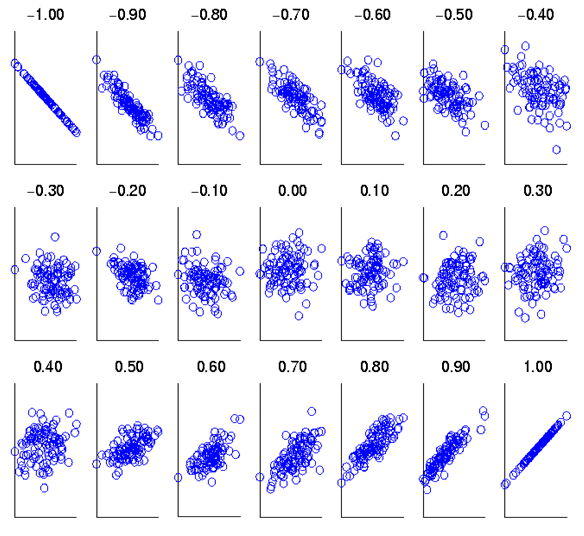

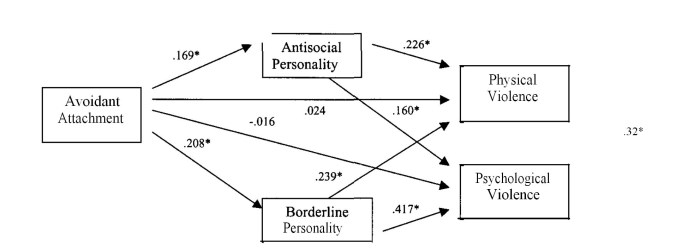

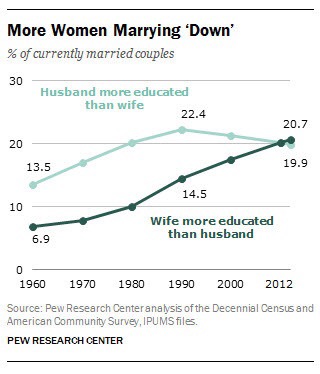

Of course, questionnaires can be used to measure and summarise mate value. It is reasonable to presume that we guard what is valuable to us, and in relationships this intention is expressed as “controlling behaviours”, which can also be reported by questionnaire. Having set the scene, we can now interpret the chart below

While women rate their partners’ controlling behaviour as slightly greater than their own (though with considerable overlap shown in the standard errors) the man having higher mate value than the woman requires fewer guarding behaviours in both genders than the reverse. Women with men of lower mate value than themselves are spending more effort on guarding them than the reverse. Guarding behaviour correlated positively with relationship length in this study, so it was an effective strategy for both genders.

Let’s look more closely at mate value. In the majority of relationships (58%) the woman had lower mate value than her partner. The results from this classic study show that men are more willing to compromise than women for short term relationships, though not for more serious ones.

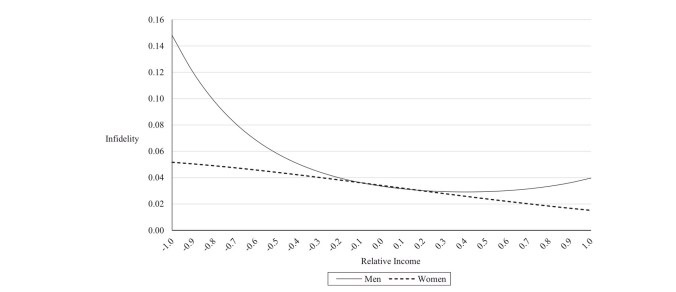

So, summary mate value is a more important sexual characteristic for men to have than women, especially for short term relationships. Compared to men, women who haven’t been able to establish relationships with men with higher mate values than themselves appear to be behaving defensively, trying to avoid a worse future partner, rather than believing their own higher mate value would enable them to do better. Astute readers will have noticed a significant portion of mate value (education, social status and career prospects) relates to societally acquired, rather than intrinsically individual properties: we have already seen that these are more important when long-term choices are being made. This interpretation is supported by the association of sexual infidelity in marriage with income inequality (considered as a proxy for mate value). The pattern of infidelity suggest that women with higher mate values have something to guard against, as well as thinking that they can’t replace their untrustworthy partners with someone better.

Quantitative differences in physical characteristics

Women are, on average, shorter than men, less strong, and can grow longer hair. What happens to men and women who aren’t gender-typical in these respects?

For height, the position is clear: being taller makes you wealthier and more powerful. While the reasons for this aren’t clear, shorter men will resemble average women more closely in the wealth and power they wield: they’ll have less of it. Consistent with what we just discussed regarding mate value, height is an important physical attractor for women, less so for men, despite the potential for women’s height to signal greater mate value as well.

We tend to think of physical strength as a bit passé when it comes societal roles

but physical strength, expressed as muscle development, is both easily observable and a more acceptable component of male than female attractiveness. Height, though attractive in itself, does not suffice alone.

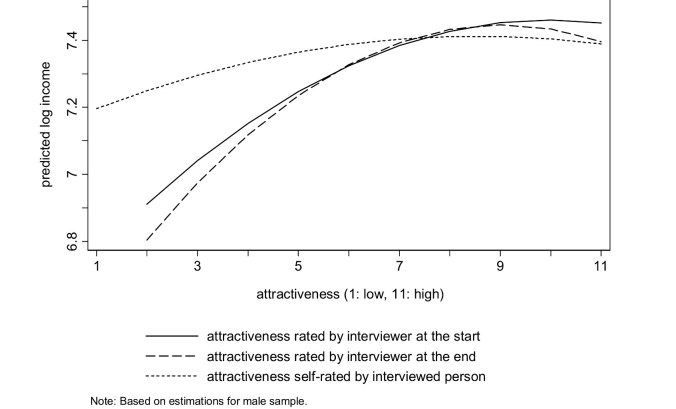

It seems that attractiveness is rather more important for men than women in obtaining good income, as these charts show.

532 Women: attractiveness is an 11 point subjective scale; income is a log scale of monthly income in Euros

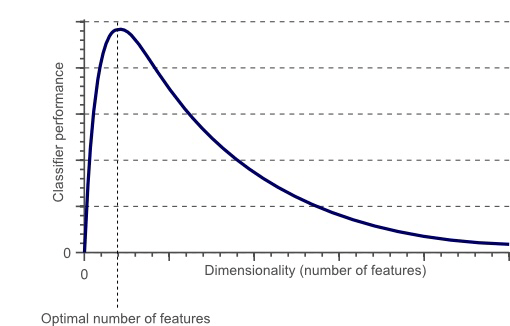

There is the expected increase in monthly earnings for women with increasing attractiveness. However, the much steeper and non-linear curve for men indicates that men are being heavily penalised for lack of attractiveness in the jobs market. Thus, the social attributes contributing to men’s mate value are correlated more closely with physical attractiveness than those in women, which increases the less attractive a man is. This is likely to produce a longer lower tail in male mate values, compared with female ones.

While the influence of long hair in men on societal roles isn’t discussed much in the academic literature, the popular press is full of it, and the issue seems to be in doubt. The direction is as we might expect. There are also suggestions that the “short hair implies less need for nurture” has been a styling (and practical!) cue employed by women wishing to adopt independent roles.

Because of the social learning model we’ve presumed as a mediator of gender roles, finding universally expressed roles does not necessarily mean that the behaviours themselves are “hard-wired” in our genes. For example, aggression is generally accepted to be higher in boys and men, though in spousal relationships there is evidence of equivalent frequency, albeit with more adverse consequences of male aggression. However, consistent with our model, a recent study found it to be mediated by fathers’ but not mothers’, differential treatment of boys and girls.

Equally, we should be careful about assuming that genetics has nothing to do with how we teach our offspring. One large study has suggested that 23%–40% of how we parent our children can be accounted for by genetic influence, and another big study has broken this down further: care is more strongly heritable than control, and adverse styles more heritable than positive ones.

Despite these caveats over cause, we seem to be able to make four claims.

- We evaluate our potential partners according to a complex scale of values, which we can summarise into a general mate value.

- Mate value is harder to observe in males than females

- We are dimorphic in how we employ mate values: perceived male values are rated more highly than female, even by women.

- The workplace scales male mate values differently from female ones, making them easier to detect, particularly at the lower end. This implies that the workplace is an important part of our reproductive as well as economic life, alerting women to differences in male mate value that otherwise might otherwise be hard to detect

Economics

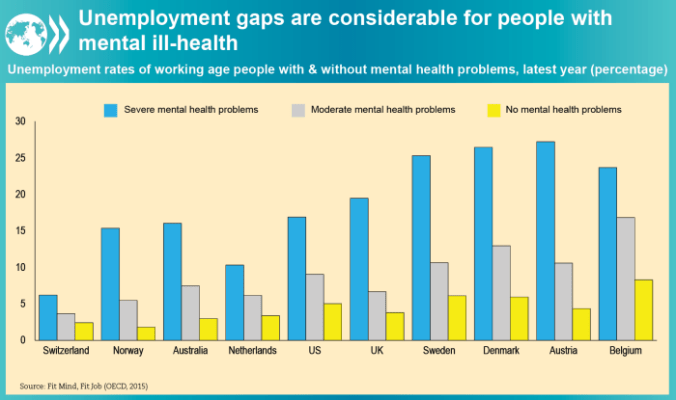

At a macro level, a powerful economic argument can be made for improving female participation in the workplace.

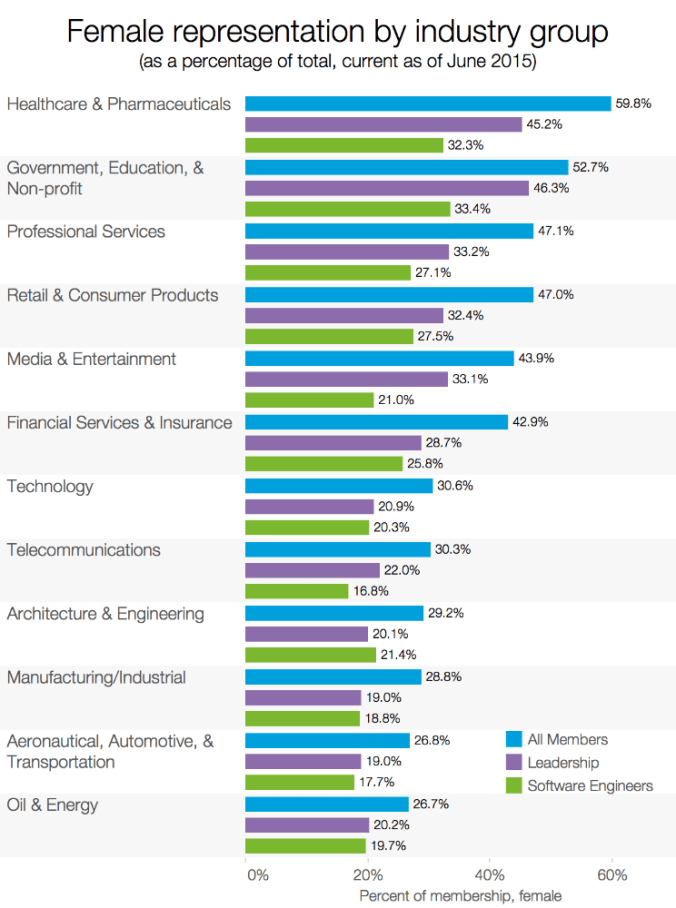

In developed countries at least, women are strongly represented, with the emphasis now shifting towards achieving equality across professions, seniority and salary.

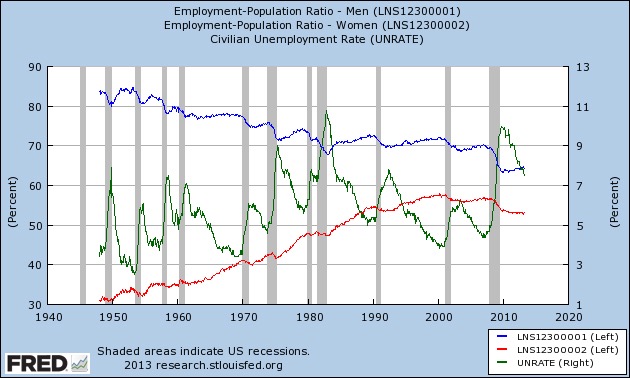

However, as the chart below shows, the increased participation of women in the workforce has led to increased competition between the genders, evidenced by the changing balance of male and female unemployment.

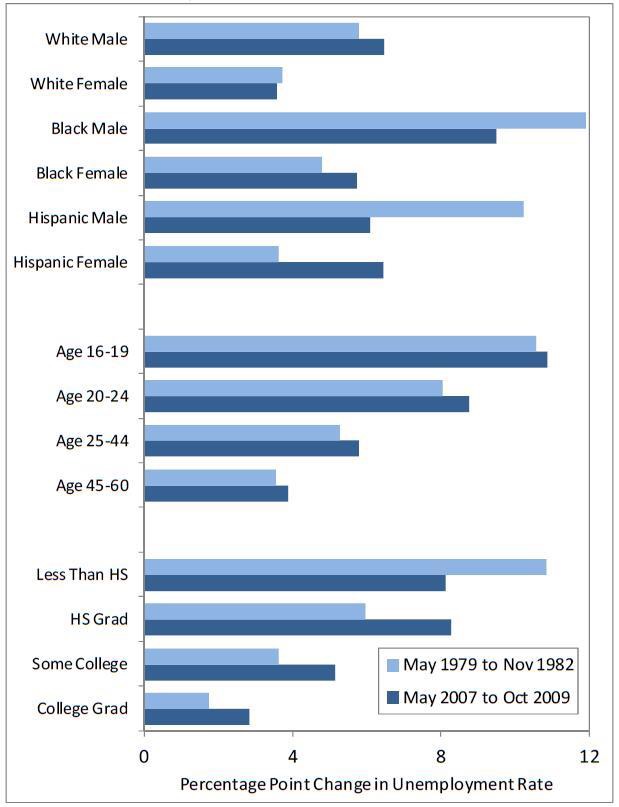

From what we have just covered, we would expect males with lower mate value to be worse affected by this and, using race as an indicator for this in the racially discriminatory US, this is what we find

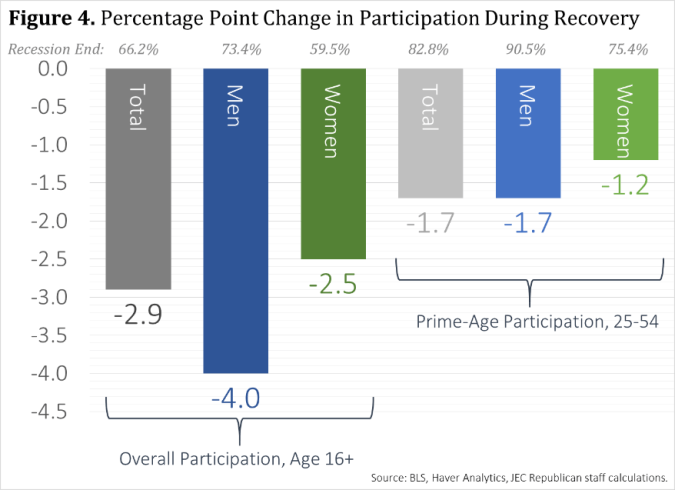

For the dimension of race, we can see that, as predicted above, men are more at risk of unemployment in recession than women, and this effect is exaggerated for black males. The picture for the Hispanic community differs for the 2007-9 recession, with equal increases for both genders. While the pattern for education is as expected, that for age appears contradictory, as younger ages would have higher mate values. However, unemployment at younger ages is more likely to reflect increased difficulty in entering the jobs market, while that in older ages will be redundancies. The increased costs of the latter, together with loss of skills, makes reductions in hiring new young people the easier choice. We can see this differential being maintained even during economic recoveryYoung men are at particular particular risk of being out of the market. Overall, in the US nearly one fifth of 20-24 year olds was neither enrolled in education nor working in 2013.

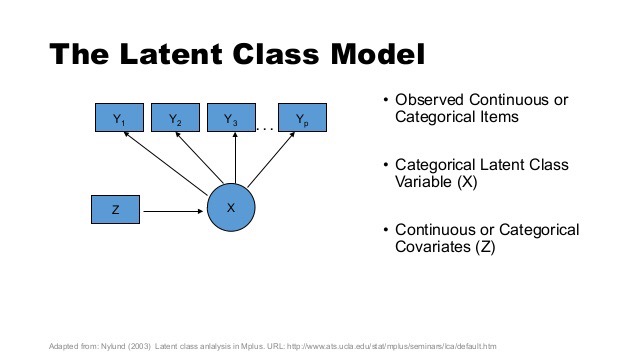

We have seen above that the labour market isn’t just about value production. It also allows women to more accurately assess the mate value of potential partners. We’ve just seen how the combination of recessionary pressure and female entry to the labour market has squeezed young people, and especially young men, out. From the above, what effects might this have?

- It seems likely that there will be an increase in male-female pairs where female mate value is greater than male. This might lead to an increase in guarding behaviour.

- As economic mate value is more important in romantic relationships, there might be a higher proportion of short term relationships producing children.

- Poorer information might lead to less stable mate choices, as random error is increased. This might be most apparent at the poorest and most discriminated end of the population, who therefore will have the lowest mate value.

In the US, the proportion of married couples where the woman earns more than the man has been steadily increasing

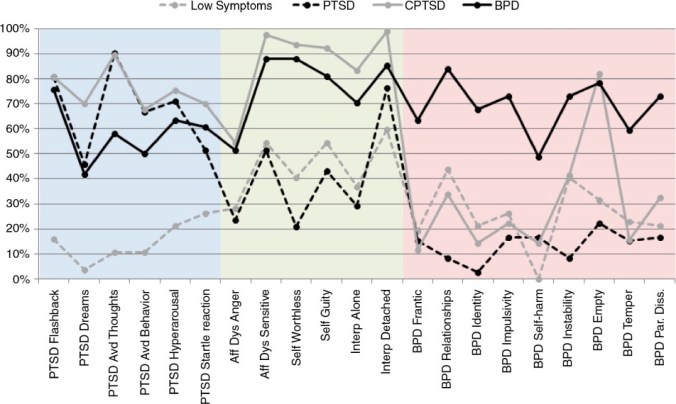

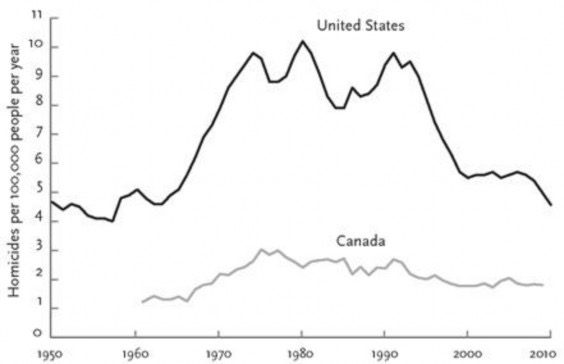

We have seen above this might promote an increase in guarding behaviour. At the extreme end, this results in domestic violence, and some data suggests it might occur as predicted

Homicide is likely to be an insensitive measure of guarding behaviour, especially among women. However, the U.K. has undertaken surveys of sexual attitudes and behaviour. It has produced some apparently contradictory results on sexual attitude change, which nonetheless fit our predictions.

- Between 1991 & 2013, disapproval of non-exclusivity in marriage has increased for both genders (18% increase for men from 45%; 17% for women from 53%). This fits our hypothesis regarding guarding behaviour, as well as validating the women’s reports of their partners in the study that discusses it: like the study, the men reported higher rates of disapproval.

- Over the same period, there has been no change in attitude over one night stands for men (20% saw no problems), but the proportion of women seeing nothing wrong in such behaviour more than doubled, from 5.4% to 13%. This is consistent with our hypothesis that mate choice for women is now more difficult.

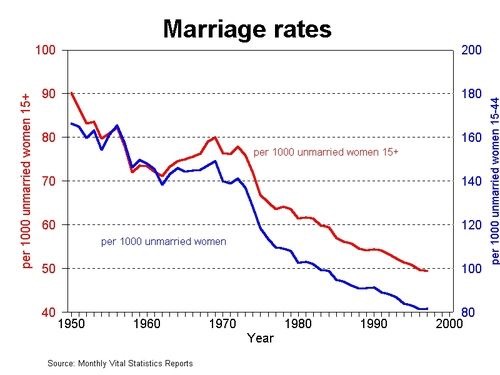

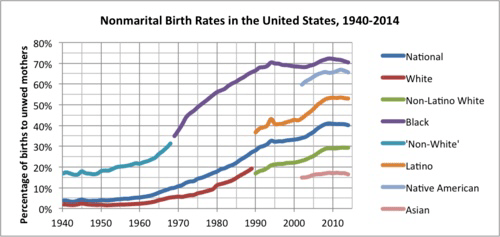

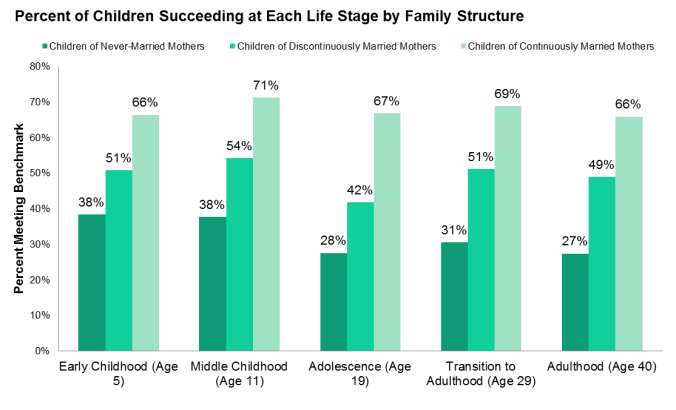

There seems very solid evidence that a higher proportion of children are coming from less long term relationships, irrespective of racial group.

The pattern of spread among the different American ethnic groups is consistent with the differential effect of losing the workplace’s long tail towards the lower end of the jobs market. It is not simply people marrying later (e.g. after the birth of a child), as this US chart shows

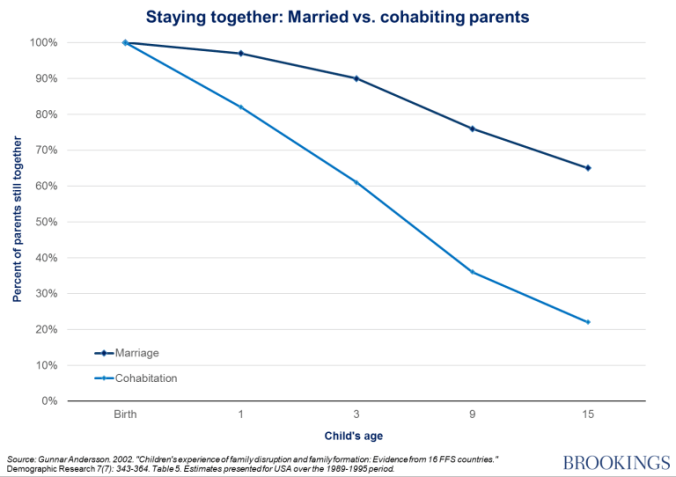

This would not matter if cohabitation was as stable as marriage, but it is significantly less stable,

consistent with our hypothesis that the reduction of information about male mate value makes it harder for women to commit successfully, as the next chart shows.

Furthermore, despite the increasing proportion of children being born to non-married women, in a variety of relationships, the number of those women who do not work outside the home has remained relatively constant, despite increasing female employment, while fewer married women stay at home. Single women are taking the breadwinner role for themselves, rather than sharing it with a man.

Unfortunately, and consistent with the problem being at its worst (given assortative mating & competition) at the lower tail of the mate value distribution, they can’t do it alone.

What does all this mean for men?

The market for male lemons

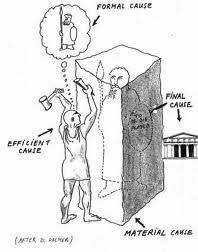

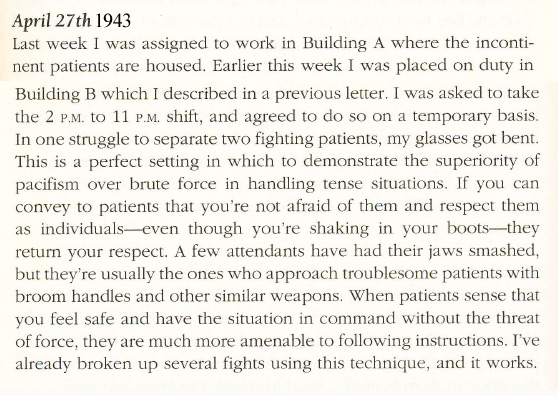

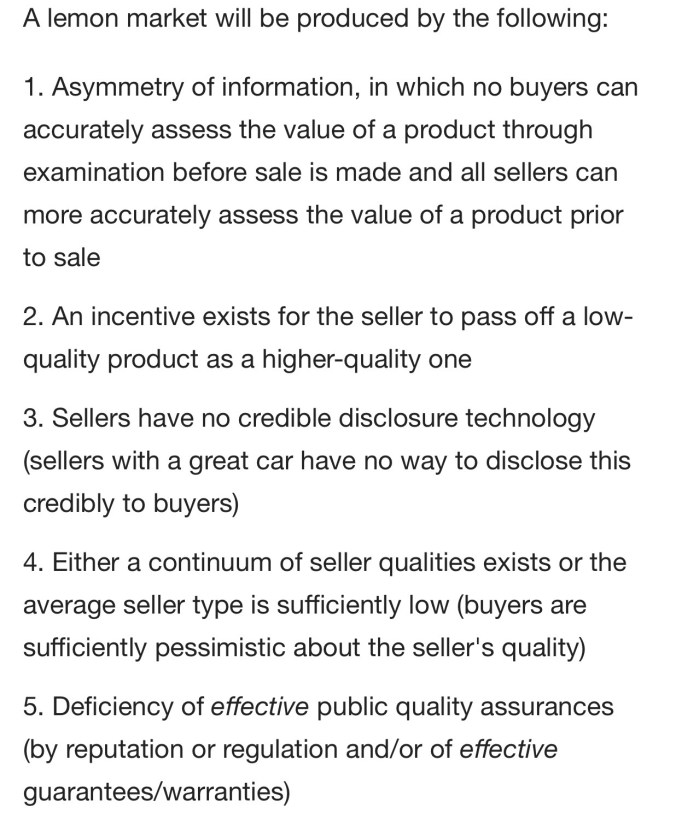

My title for this subsection derives from a famous economics paper “The market for lemons: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism” by George Akerlof. He discussed what he called “information asymmetry” in the second hand car market, which enabled the sale of “lemons”: cars which proved defective only after being bought. When market information is asymmetrical, only the seller completely knows the value of the goods; the buyer has to make a (maybe educated) guess. He set out the conditions for such a market as follows.

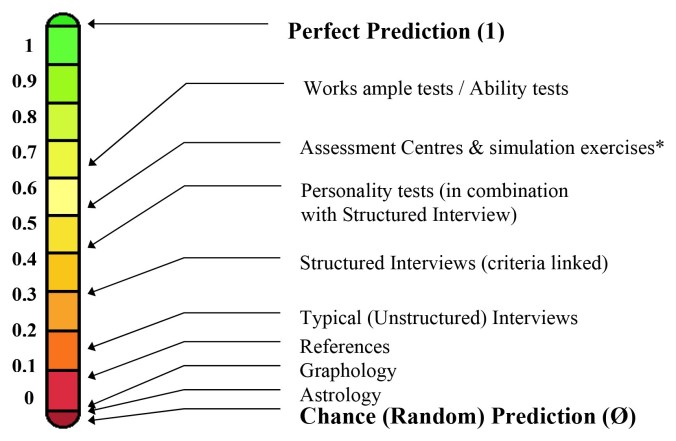

The argument we have just constructed suggests that the workplace functions to help provide men with a clear “disclosure technology” for their mate value and this has been impeded, especially regarding men with the lowest value.

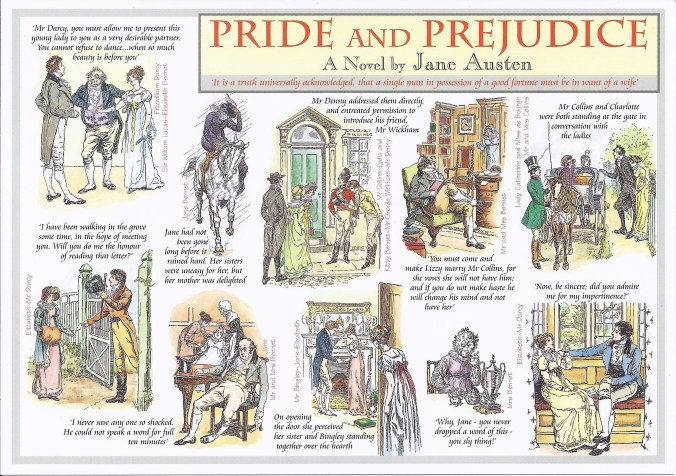

Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice” describes how information about mate value was transmitted in the early 19th Century.

We can see how the economic and social aspects of everyone’s mate value is either public (as a result of gossip or family connections), or exposed at gatherings (balls) designed for that purpose.

Staying at the top of society, we can see the same process operating at the “London Season” with its debutantes’ balls,

which still continues today. While males who deceived over their mate value are well described by Jane Austen, the system was designed to expose them as much as possible. Outside (and even inside) those exalted circles, things are much harder now

as greater equality combines with less workplace (or family) information to keep men’s true mate value hidden.

It seems like we have created the conditions for a market for male lemons (we have seen that women’s mate value is less significant). Akerlof found that, under those conditions, the buyers (women) apply an averaged discount across the whole market, so “peaches” (the opposite of lemons) get undervalued, while “lemons” are overvalued. In Akerlof’s model, owners of peaches walk away, while lemons pile in: here, because it’s reproduction, which is necessary for everyone, even the peaches will stay around. What might we expect?

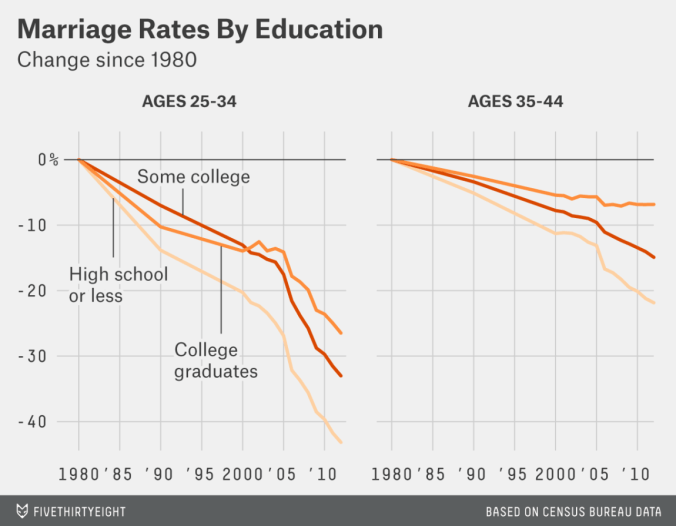

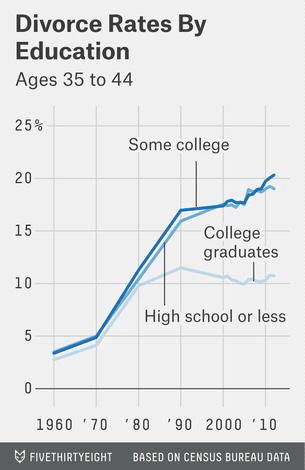

If women are less able to tell the difference between a peach and a lemon, they will maximise their chances of getting a peach by enlarging their pool of available men, and resampling as required. This effectively increases competition between women, as larger pools means more overlap. For male lemons, this is great news, as, unfortunately for the women, their pool of available women has grown. This will be equally true for peaches, who will therefore also have a larger pool of women to choose the very best reproductive partner from. Using marriage as a proxy for this, and education as a proxy for the social aspects of mate value, we find those with more education showing a slower rate of marriage decline,

and a complete decoupling from the secular increase in divorce rates

Unlike their female peers, male peaches are doing well.

Implications

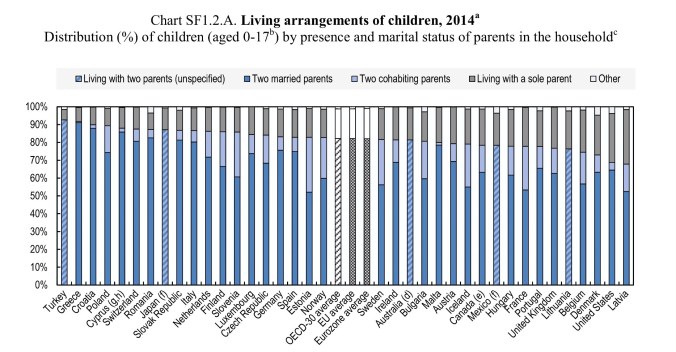

I have stuck to a single country to cover the economics because it allows comparison of the figures. Countries do differ in absolute statistics

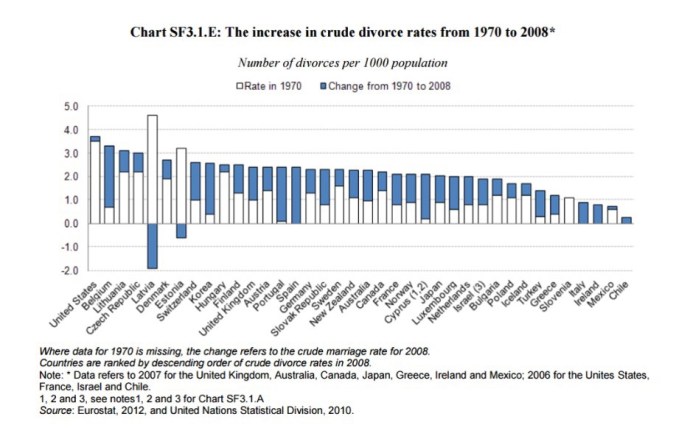

and the OECD chart above shows that the US has the second largest number of single parents among developed nations. However, as the next chart (of divorce rate changes) shows

the tendency is for even marriages to become less stable with time, with cohabitation being worse. The picture is similar: unsurprising, given the common approach to workforce gender balance across OECD countries.

It seems that women are responding rationally to the loss of information from the workplace about potential partners.

- They are probably guarding the partners they have more tightly (at least, if they follow through on their attitudes)

- They are more prepared to have sex, and therefore risk offspring, with less permanent or even casual partners.

- They provide for their offspring without partners.

While this strategy makes sense, there are costs.

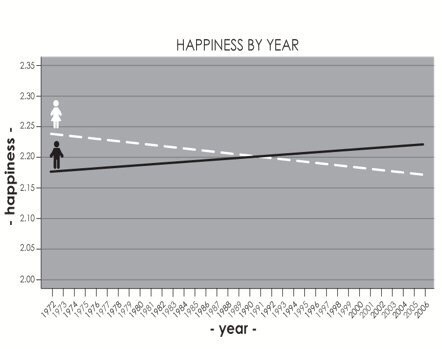

The impact on children is well-known, of course. What is less known is that these trends have also been associated with a decline in female happiness, even though men’s has increased.

While this graphic refers to the US general social survey, this result pertains across OECD countries

However, the argument we have just developed has suggested a paradoxical consequence to the progress of female entry into the workplace. The unavoidable displacement of male jobs through female competition has deprived women of a key tool in assessing male mate value, which has worked to men’s advantage. Given the importance of reproduction in our lives, the different trends of male and female happiness are consistent with our expectations.

It does seem that the triangle we have explored does need squaring, but it is not easy to see what the solution might be. Returning to the days of sexual inhibition, work restrictions and formality is no recipe for female happiness at the individual level, and is destructive of our wealth. The men who have benefited the most from this (the peaches) have only slight incentive (their daughters’ future) to lose the reproductive advantage these changes have given them: their marriages are nicely stable, so their own male offspring are less affected, and they experience the advantages before, through their daughters, they face the risks. The lemons are simply grateful for more access to more women. Nonetheless, our children require this problem to be solved, so an alternative way of evaluating male mate value needs to be found.