For those who find the image below distressing, I’ve explained my choice at the end.

Last winter, I had to diagnose a young woman with an eating disorder as also having a Borderline Personality Disorder (aka Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder). A capable researcher, she had googled her own symptoms, so was unsurprised, but despairing. By the time we had discussed current views in treatment and prognosis, we both had tears of relief in our eyes; hers because my take on her diagnosis gave new hope of recovery, mine because I was able to overcome the incorrect stigma the diagnosis carries. This blog is about trying to strip that stigma from these unfortunately named diagnoses, so that they can be used better.

Personality as Our Soul

Almost no-one reared in a Christian environment will have trouble interpreting this image: folks struggling to get to heaven, encouraged by angels and saints, but some being dragged to their doom by pesky demons. We know they’re not people’s physical bodies, but souls, as they look the same at the top of the ladder (heaven) as they do at the bottom (earth): there is no sign of them leaving a physical body. We also know that the demons are being fair in their choices and actions. or the saints and angels, let alone Jesus, would be intervening. When we look at the souls, we can see that they still have the characteristics and identities of the living people they once were. Though other faiths take different views, the Christian conception of the soul is thus very similar to our everyday understanding of personality. In Western philosophy, personality was a metaphysical concept, synonymous with moral character, which only recently acquired an empirical dimension. This concept can also be found in law, with new offenders having been said to have “lost their good character”, which in turn affects their ability to access certain societal benefits, e.g., it can bar immigration, and restrict jury service. I am therefore going to suggest a rather strange everyday interpretation of personality, which will however be very useful in understanding why “personality disorder” gets under so many people’s skins, and which I think captures the moral nuances of the term.

Personality encompasses those aspects of ourselves about which we make moral judgments

From this perspective, a diagnosis of “personality disorder” carries within it a potential negative moral judgment.

Personality as a psychological construct.

Let’s now take a different perspective and definition. Here’s the currently agreed psychological one

Personality refers to individual differences in characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling and behaving. The study of personality focuses on two broad areas: One is understanding individual differences in particular personality characteristics, such as sociability or irritability. The other is understanding how the various parts of a person come together as a whole.

Our technical definition has completely removed the ethical dimension apparent in our everyday approach. Instead of our personalities being something metaphysical, they are simply either a class of individual differences, or an estimate of how our various characteristics integrate with each other. This makes personality disorders no more than a subset of all psychiatric disorders, referring to some disabling disturbance in these characteristics.

However, despite these differences, both definitions have the potential to overlap upon at least some of the same qualities. For example, “trustworthiness” is a quality on which individuals may differ, and which has a clear moral valence.

Where we go from here depends very much on the assumptions we make on mind and brain. If we assume that the mind is in some way non-physical, then we have no difficulty: we simply assert that the ethical dimension of personality belongs to the non-physical part of mind, and is separable from psychiatric disorders, which reflect brain disturbance. Of course, that gives us other problems, which I’ve discussed in a previous blog post on this site.

If however, we do accept that mind is simply how the brain organises part of itself, then we have to admit the possibility of psychiatric disorders existing which will attract negative moral judgments, even though we agree that psychiatric disorder should not be subject to such judgments. It follows that this is exactly the cleft stick we find ourselves in with personality disorders.

Personality Disorders as Psychiatric Diagnoses which Attract Negative Ethical Evaluations

It was not so long ago that all psychiatric disorders were morally connoted. The combination of early developments in genetics with hybrid terms such as “degeneracy” (implying both physical and moral decay within or across the generations) led to possibly the worst ever failure of the medical model: eugenics, which still casts its shadow over biological theories of mental illness.

We now know that eugenics was genetically as well as morally misguided, but does that mean that there are no biological failures of “moral character”?

The strange story of gambling.

Curiously, for so enduring a vice, gambling (unlike greed) isn’t mentioned in the Christian Bible, though it does make it into the Koran. Excessive indulgence in it has been correctly associated with the complete destruction of family fortunes

Historically, it has also been associated with companion vices of promiscuity and intoxication, making it a fine topic for instructive paintingsHowever, there is another side to this story.

Parkinson’s disease is a neurological condition, named after the doctor who first described it, which induces tremor, interferes with movement, and can impose mental, as well as physical inflexibility, with dementia as a severe consequence.

Its mechanism is reasonably well understood

and it’s long been treated, with some success, with drugs that increase dopamine levels, most famously dopamine’s metabolic precursor, L-DOPA (called levodopa when prescribed).If we look on its list of side effects, we find

It turns out that dopamine does more than let us move properly. It also is the major neurotransmitter for the brain’s reward system, amongst much else.

ACC Anterior Cingulate Cortex; PFC Prefrontal Cortex; NAcc Nucleus Accumbens; HC Hippocampal Complex; VTA Ventral Tegmental Area

The key bit that concerns us here is the Nucleus Accumbens, falsely called the brain’s “pleasure centre”; it’s probably better described as the brain’s encouragement centre. The relationship between it and dopamine can be summed up as

Anything that puts up dopamine in the Nucleus Accumbens is something we want to do more of, and the more we do it the more dopamine levels there will rise.

To show this, here’s what happens to our brains when we gamble

If we compare this picture with the map of the dopamine system above, we can see the Nucleus Accumbens is highlighted. The L-DOPA story shows that the same relationship can also work in the opposite direction. It’s also been found that the effect occurs when particular genes encoding a particular type of dopamine receptor DRD4 is present. These last two studies were not done on folk with pathological gambling. so we are talking about ordinary genetic variation in ordinary brains. Our worst fears are realised: moral behaviour is just as dependent on brain states as anything else we do. If so, then impaired mental health could disrupt our moral functioning, and not just as a result of being cut off from reality.Mental health and moral responsibility in society

Our everyday notion of moral responsibility assumes freedom of will, and the latter seems necessary for retributive justice. However, brain states are about anatomy and biochemistry: things determined and irrelevant to “will”. One could argue that this, as much as religion, has encouraged a dualist approach to mind: our brain is the horse, but we are the rider, and while it might throw us from time to time, we are still responsible for what we make it do.

This lets us try to judge whether the brain has thrown its rider, or whether the unacceptable conduct was the rider’s decision. However, as we have already assumed that states of mind are no more than expressions of brain states, we have to reject this as a convenient fiction.Fortunately, we don’t have to mire ourselves in the intricacies of the relationship between moral responsibility and freedom of will. Instead, we may simply claim that it wouldn’t be fair to treat differently functioning brains the same way. If we build on my previous blog about brain-mind identity, and assume that diagnoses are imperfect but useful indicators of systematic and impairing differences in brain function, then diagnosis may be used to guide us.

Let’s start with our formal statement of the identity hypothesis, as developed in that blog.

“For every state of mind (∀M), any individual state (Mi) can be mapped to a particular state of brain (Bi), contingent on that brain’s characteristics (Vi)”

In symbols, we write

∀M(Mi ≡ Bi) | Vi

Let us assume, with English law, that criminal (or vicious, it doesn’t matter which in this context) requires both an evil intention and its related action. All our vicious and evil intentions (let’s call them wicked) {W} are part of {M}, so, allowing someone to be anything up to totally vicious and evil {W} ⊆ {M}. Furthermore, our definition allows us to assert that a wicked intention includes the wicked action in terms of brain states, otherwise it wouldn’t have been wicked (because we would have rejected it and done something different). This enables is to write, for a wicked intention/action

Wi ≡ Bi | Vi

Remember, Vi is the relevant brain condition i.e., the brain organisation that makes Bi possible. It therefore follows that {Vi} includes the brain state associated with any relevant diagnoses {Δi} which in symbols is {Δi} ⊆ {Vi}. Also, the relationship between Vi and Bi is one of conditionality, not causality.

Unfortunately, neither Vi nor Δi are directly accessible to us, so we have to make do with the admittedly imperfect proxy of descriptive diagnosis itself Di. Because it’s the best we have, we write

Wi ≅ Bi | Di

This means that no diagnosis can be held to cause a wicked act. To see the implications of this in action, let’s look at something that used to be thought wicked, but is now more accepted: suicide. People may choose to take their own life for a range of reasons: we also know that suicidal intent is one of the most dangerous symptoms of depression. However, it makes no sense to claim that what we normally understand an intention to be can also be a symptom, as a symptom is no more than an expression of a pathological brain state. It would be like saying that snow or interference in the picture of a badly tuned TV was part of the programme.

This means that, if we decide someone’s suicidal intent is a symptom of depression, it is pointless to debate whether they “really want” to do it, any more than someone “really wants” to have a headache. It’s there in the same way that the headache is. As wickedness requires both act and intention, we can assert that the suicide was a fatal outcome of depression’s brain state, so not wicked, irrespective of our views of suicide otherwise. Why have I said “outcome” and not simply claimed that depression caused suicide? Because it hasn’t, as our symbol-writing has shown. The correct term for what’s happened is called “moderation”, as I’ve explained in a previous post on this site. Let’s look at what all this means for how we should treat people with psychiatric disorders in general, because that’s what we’re discussing right now.- people should be held to account for Wi ≡ Bi.

- How they should be held to account should be influenced by Di.

This seems to fit comfortably with current approaches to forensic mental health, so is unlikely to be far wrong.

What our model has also shown is that, once we accept the admittedly uncomfortable idea that our ethics simply reflect a set of brain states (which we possess for excellent reasons) and can therefore become disordered like any other brain state: –

- There are no grounds for awarding a different moral status to those with personality disorders, from those with any other disorder.

- Equally, the nature of the cause of the disorder, be it trauma, deprivation or genetic variability, makes no difference to disorder’s moral status, because no disorder can have one.

Some may well recognise this as being one way of stating the principle of Parity of Esteem. As the brain is an organ of the body, we should no more morally evaluate disorders of the brain than disorders of the liver.

Understanding the symptoms and signs of personality disorder

Let’s see what happens if we try to make sense of personality disorders as just another kind of psychiatric disorder.

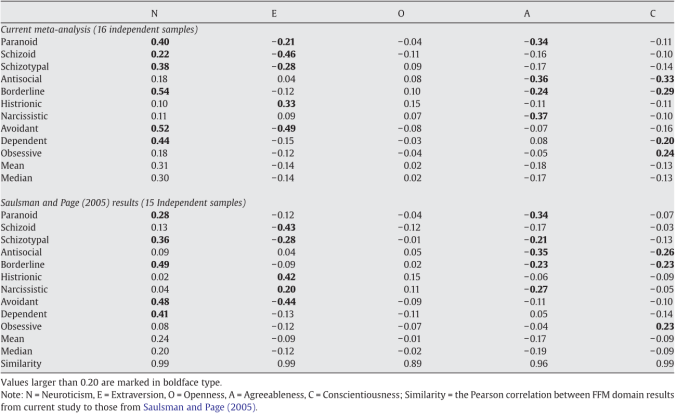

Currently, personality is described in terms of 5 overarching qualities, easily remembered if we use the acronym OCEAN

- Openness

- Conscientious

- Extraversion

- Agreeableness

- Neuroticism

However, as I’ve argued previously on this site, the value of diagnoses for clinicians and patients lies in their predictive validity, which is how good they are at letting us know what to expect from them, and what will best work to ameliorate their impact.

Borderline Personality Disorder is a good example to take. I’ve already mentioned it can be successfully treated in the introduction. Here are its symptoms

No-one wants to go through life in that way, so being able to reliably identify it, and thereby discover what’s needed to prevent it as well as treat it, would be good. In fact, it can be identified very reliably indeed, and its epidemiology can be explored like any other psychiatric disorder; nothing special is required.

We can also go a bit further, and visualise some of Δi.

Meta analysis of differences in amount of grey matter HC = Healthy Controls BPD = Borderline Personality Disorder

For BPD at least, our model fits, and this is the commonest personality disorder presenting in psychiatric clinics.

Denial of Personality Disorder is Unethical

Not so long ago, we thought that the best way to stamp out racism was to become “colour-blind” and simply enforce a rule that black skin tones meant nothing. We found it didn’t work.

- Thanks to previous discrimination, black people had inequality of access to qualifying characteristics for rewarding roles in Western society.

- Black skin tone reflected a different cultural identity & different physical needs, from haircare to health risks, none of which could be accommodated in a colour-blind approach.

The denial of personality disorder as a diagnosis has identical effects to the colour-blind approach to racism, and does at least as much harm.

Let’s do the theory first. Personality Disorders are simply a subset of {Di}, which means, conditional upon the diagnosis. their symptoms shouldn’t be subject to moral censure. However, we have already seen that, in the everyday theory of personality, their symptoms are exactly those characteristics which are likely to lead to moral judgments. So, in the absence of a diagnosis, we will assume that the person is culpable in the same way as anyone else, which we have already argued is unfair.

Instead of being symptoms, the overweening arrogance of narcissistic personality disorder, the dependency and unreliable emotional expression of BPD, and the aggression of antisocial personality disorder become invalidating moral defects, leading us to avoid, criticise or punish the sufferer, rather than helping them overcome their disorder. Sadly, this view also holds away amongst some ill-informed (and sometimes would-be) professionals, included in the view that “personality disorder isn’t a psychiatric disorder”. For example, it is currently fashionable among some psychiatrists and psychologists to claim that President Donald Trump has a narcissistic personality disorder. However, it is clear that this is deliberately using the stigmatising power of the term for political ends. This abuse arises precisely because these psychiatrists and psychologists are blurring the distinction between everyday and technical definitions of personality and its disorders, so hiding the distinction between the brain state associated with narcissistic personality disorder Δi, and his inflammatory pronouncements (Wi ⊂ Mi) ≡ Bi. This is not a diagnosis, but an insult: the diagnosis is being recruited as a synonym for ordinary wickedness, and its separate validity denied in consequence. This is also why proper assessment (which was not conducted by Trump’s accusers) is essential for all psychiatric disorders; it is what lets us distinguish between Mi (or Wi) and Di in the first place

While little research has been done, narcissistic personality disorder sufferers make significantly more lethal suicide attempts than other personality disorders, and are also amenable to treatment, though research is also more scarce than for BPD. From this perspective, if they’re right, the accusatory clinicians are (probably minimally) harming rather than improving Donald Trump’s life expectancy and quality of life. Far worse is the barrier this creates for those who suspect they might have this, and take the attack to reflect how professionals might treat them. As the two images above show, they may very well be right. Under these conditions, it is understandable that service users with personality disorders may eschew and ridicule these diagnoses. However, they may unwittingly be helping to perpetuating the very prejudice they are trying to fight against, and make it harder to get help which can literally be life-saving, for themselves and others.

I have always taught my students that the nature of psychiatric disorders means that they can be hard to be with. This is especially true of the personality disorders, and is one of the reasons they can be so hard to treat. However, we have seen that we have no ethical reason to judge folks with personality disorders more harshly than those with any other kind of psychiatric disorder, and failing to recognise and treat them as psychiatric disorders makes us more likely to do so.

Why “Silence of the Lambs”

Since the blog was published, I’ve had several comments arguing that this image was both distressing, and maintained the very stigma this blog post opposes. I’ve removed it from the title screen, but have kept it as my initial image, setting out my reasons for choosing it, rather than simply replacing it with something more inoffensive.

- As you’ll have realised if you’ve read this far, this blog is about all personality disorders, and that is the everyday perception of them. Though fictitious, Hannibal Lecter challenges us to realise that he has a psychiatric disorder, and it isn’t always easy to find it in ourselves to accept that those as bad as he need help as well as punishment. The alternative is to talk of “better” and “worse” personality disorders in moral terms, and if you’ve followed my argument that would never do.

- Hannibal Lecter is also a psychiatrist. The idea of the deadly, dangerous amoral psychiatrist who sacrifices people for knowledge continues be fed to us in the media, and sadly reflects social contagion from these patients, who we do our best to treat.

- In the picture, Hannibal Lecter is restrained. No-one who commented to me has mentioned the level of restraint, but it is outrageous. It brings home how much training is actually needed to treat this class of patient humanely. The film itself flags the inhumanity of his confinement, when untrained staff were in charge, but, for someone with a personality disorder, we read it as a sign of what he needs or deserves, rather than cruelty towards him. It is high time our attitude changed.

Found this excellent article via Dr. Carol Henshaw, who tweeted it. Found it very interesting.

I was honored that Dr. Henshaw wrote the foreword to my book “Birth of a New Brain – Healing from Postpartum Bipolar Disorder,” (Post Hill Press, Oct. 10th) and if she retweets something, I pay attention!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! Ok so a lot of it was above my comprehension. I got lost on the symbols and data. However what I did understand was very interesting.

I won’t tell fibs, and say the thought that Trump has some form of mental illness, hadn’t crossed my mind. I actually feel guilty as I myself am thusly perpetuating the stigma, that I so wish to eradicate. I agree too that such stigma reinforces to people that have the symptoms, may be reluctant to go and chat to a doctor about it, for fear of ridicule etc.

I had a point or a question I wanted to ask, in regards to the paragraph about suicide, but like Elvis t has left the building.

I do have one question though and this is in regards to a particular form of treatment. I’ve read and heard from people for and against medication being used as an effective treatment for PDs, specifically BPD. Also on the BPD support groups it is a much debated topic as to whether or not meds work for the illness.

Again wonderful post. And I will be tweeting it as I think some of my followers will find it interesting too.

Best wishes Stella-Rayne.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a thoughtful reply! If you go to the first post and have the patience to plough through, you should get a handle on the symbols (I do try to translate them into English: when you read some of the translations you’ll realise why I use them!). In answer to your question, all a diagnosis can do is to define a group which might respond to a treatment: it doesn’t in itself tell you if that treatment is going to work. If you keep reading forwards in my blogs, you’ll find one on how to make sense if the clinical trials you should always look for when someone starts claiming that a treatment works for some condition. Again, many thanks for reading my blog so carefully

LikeLike

Pingback: Borderline personality disorder diagnosis: helpful or harmful? – Health Top Daily

Pingback: Borderline persona dysfunction prognosis: useful or dangerous? – thespiritualmental.com

Pingback: Borderline personality disorder diagnosis: helpful or harmful? – Health Conscious